As he sat on the grass and looked across the river,

a dark hole in the bank opposite, just above the water’s edge, caught his eye,

and dreamily he fell to considering what a nice snug dwelling-place it would make

for an animal with few wants and fond of a bijou riverside residence,

above flood level and remote from noise and dust.

As he gazed, something bright and small seemed to twinkle down in the heart of it,

vanished, then twinkled once more like a tiny star.

But it could hardly be a star in such an unlikely situation;

and it was too glittering and small for a glow-worm.

Then, as he looked, it winked at him, and so declared itself to be an eye;

and a small face began gradually to grow up round it, like a frame round a picture.

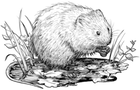

A brown little face with whiskers.

A grave round face, with the same twinkle in its eye that had first attracted his notice.

Small neat ears and thick silky hair.

It was the Water Rat!

The Wind in the Willows

Kenneth Grahame (1908)

Around 10,000 years ago, after the ice sheets retreated from the last Ice Age, black water voles from southern Europe made an epic journey across an ancient land-bridge and began to colonise Britain. Several thousand years later they were pushed north by the brown water vole from the Balkans. Eventually, the black water voles settled in Scotland and the brown water voles settled in England and Wales.

In the early 1900’s, a water vole sighting was an unremarkable event woven into the lives of country folk who gazed upon these ‘water rats’, as they were then known, with deep affection. In this nature connected period almost everyone could recognise one, because they were part of the fabric of their childhood. There were 8 million of them! They were widespread and commonly heard or seen in almost every slow flowing waterway in the British Isles, from the extremities of Scotland to the tip of Cornwall. Although absent from Ireland, the Isle of Man and the Scottish islands, they were present in Anglesey and the Isle of Wight. They were so ubiquitous that in 1908 ‘Ratty’ became a celebrity as one of the main characters in Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows.

Sadly, this fame did not help water voles. During the first world war, humans removed bank-side vegetation for crops and let cattle trample their banks and homes. Then intensification of farming for food production started during the Second World War which caused habitat loss, fragmentation and further degradation. Their decline increased significantly when American mink escaped from fur farms that started up in the UK in the 1920’s, due to demand for mink coats. By the 1970’s, there were 800 mink farms in Britain. Some farms had as many as 5,000 mink and some managed to escape. Their numbers in the wild rose steeply when many mink were released from fur farms by animal rights activists in the 1980’s and 90’s. A breeding female mink is small enough to enter water vole burrows and will cause the extinction of a water vole colony in one breeding season. Non-native species are often disastrous for finely tuned ecosystems that have evolved over time and the American mink is no exception.